In Conversation with Daniel John Corbett Sanders

We sit down with Daniel John Corbett Sanders to find out more about their exhibition at RM Gallery, Urban Nothing, and plans for the months ahead.

Becky Hemus: You described the exhibition to me as “queer narrative documentary,” something that I thought was interesting given that the paintings are so stylised. How do you define the concept of documentary in your work? Are the images a montage of recollection, or frames of specific moments?

Daniel John Corbett Sanders: The paintings in Urban Nothing document the lounge of the cruise club I work at. Cruising is a quest for sexual encounters in public spaces and, like flânerie, is a method I employ as a documentary technique used for a queer interrogation of urban space.

It is a narrative technique, and plots the city-on-the-move and the transitory faces of city spaces, in this instance a cruise club. Instead of reiterating the dominant narrative of progress, cruising narratives document collisions between urban gentrification and sexual emancipation, between embourgeoisement and bohemianism. I try to cruise the contradictions of urban development and face the catastrophes of history, and for Urban Nothing it was important for me to use painting to document and personify narratives of my experiences and memories in order to undermine official history, and shake off conventional ideas of genre, temporality and identity.

The figurative sculptures are particularly incredible, the pull between materiality and form coalesces in an interesting way. What was the process of making these? I think that you said they were “gross,” which made me look at the works list and realise they were made of rubbish.

They’re literally trash taped up and painted as ruined old men. When I say trash, I mean the cum tissues and “lube-stained” newspaper from my cleaning routine at the cruise club. They’re probably a public health hazard, but so are most sculptures of white men. They’re decaying in front of you, the tape is coming undone in the heat and the skin is flaking off.

At one point the statues of Roman bathhouses were painted and colourful, but with weather and time, the paint peeled away leaving a whiteness we only recently learned was a myth. When the superficialities are stripped from the men in Urban Nothing, all that will be left is the trash that made them.

I’m thinking here also of exhibitions such as After Jack, which we worked on together when I was at Window Gallery in 2018. You transposed detritus from your workplace and scattered it on the floor of the exhibition space—but the elements inevitably looked very different in the vitrine-like box of a university gallery than they did in their initial surrounds. Was there an element of fiction here, or were all the materials actually collected from your job?

Yes, the materials in After Jack were sweepings from the floor of the cruise club I work at. For this show I purposefully refused a floorsheet so there’s definitely an element of fiction happening when the audience imagines the origin stories of an apparently random assortment of trash in a window at the University of Auckland General Library.

For me at the time, this was an experiment in working with, exhibiting, and protecting hidden histories. Given queer historiography is a fairly recent contribution to academia, you are more likely to find an expansive archive of queer history in the trash of a cruise club than in the university library. I also relate more to the used tissues, condoms and spilt coffee I clean up at 3am than I do to the glitz and glam of the city. For me, the detritus portrayed an unflinching homosexuality, an abject eroticism, and it is here I feel at home.

Urban Nothing explores the space of queer bathhouses as a microcosm of late capitalism. Can you delve more into this? Does the exhibition reflect inner-city reality more broadly?

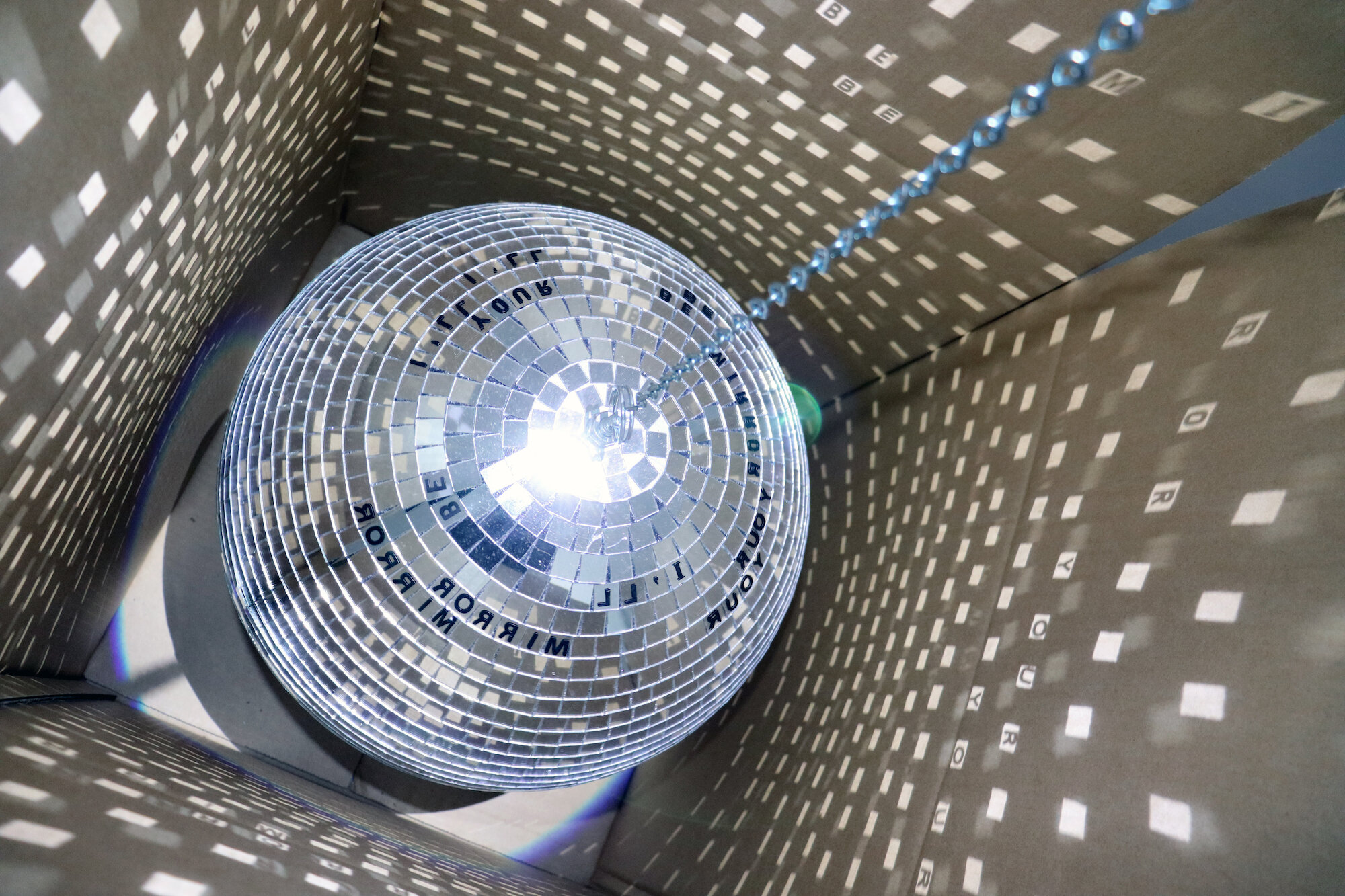

Common idealistic and nostalgic gay historiographies look to gay bathhouses as being at the centre of gay city life — as the first spaces to offer gay men a site of congregation, spaces that transcended class difference in their naked anonymity — and paved the way for new social praxis.

Such historiographies also mark the demolition and dilapidation of gay bathhouses during government responses to AIDS as signalling the end of radical and vital experiments in urban living. But these historiographies are haunted by erotic radicalism and economic progressivism that are two sides of the same coin of gay liberalism.

When only viewed in such a liberal, idealising, perspective we lose sight of real, weighty, material contradictions. Urban Nothing, and my overall practice, attempts to draw out these contradictions and hold them in contrast to the histories of the gay bathhouse that overlook them in favour of the myth of a lost utopia (such myths have paved the way for colonial projects like Israel—see Jasbir Puar’s texts on homonationalism).

You also run Parasite, an artist-run gallery prioritising the exhibition of LGBTQ+ artists. The gallery sits in a nee-brothel on Karangahape Road, with exhibition spaces that wind along narrow corridors in a cube-like spiral formation until they reach an apex that annexes to your current apartment. You literally need to journey through the gallery to come home. Within this framework, how do you see the coalescence of your role as a steward (for artists), and position as an artist yourself? I note that many artist-run initiatives function as a platform to showcase the facilitator's own practice, but so far you have kept your curatorial and artistic output separate.

Parasite was born out of necessity, in many ways, and occupies a complicated position in the art world. One of these complications is its complicity in contributing to a cultural sterilisation in the Karangahape Road area it is based, by way of adding to the narrative of cultural progress. Though necessary, art is guilty of this, and so are visible notions of Pride, but undeniably these progressive narratives are tools that are used to fuel urban development that has, and has had, devastating consequences for more marginalised people and businesses, especially some LGBTQ+ and sex industries in the Karangahape area.

I don’t make any separation between the labour I do in my artwork, with Parasite, and the labour I do at my places of employment, including the cruise club. I see them all as necessary means to move through the world.

We are also working on another project together—In Residence at the Auckland Art Fair, a section dedicated to artist-run spaces. How important do you think it is for Parasite to be present amidst the very bourgeois setting of the Fair?

It is important to demonstrate LGBTQ+ excellence to the art market and subsequently show the market that Parasite and our artists, and LGBTQ+ artists across the board, are leaders in contemporary art that are well worth investing in.

“I try to cruise the contradictions of urban development and face the catastrophes of history, and for Urban Nothing it was important for me to use painting to document and personify narratives of my experiences and memories in order to undermine official history, and shake off conventional ideas of genre, temporality and identity.”

Urban Nothing runs at RM Gallery through 13 February 2021

Connie Brown on Zoe Thompson-Moore’s Open-field; RM Gallery, 23 November - 17 December