A conversation between Bronte Perry and Daniel John Corbett Sanders

This interview has been re-published with permission from Artspace Aotearoa, originally commissioned on the occasion of the artwork commission Guilty Pleasures by Bronte Perry.

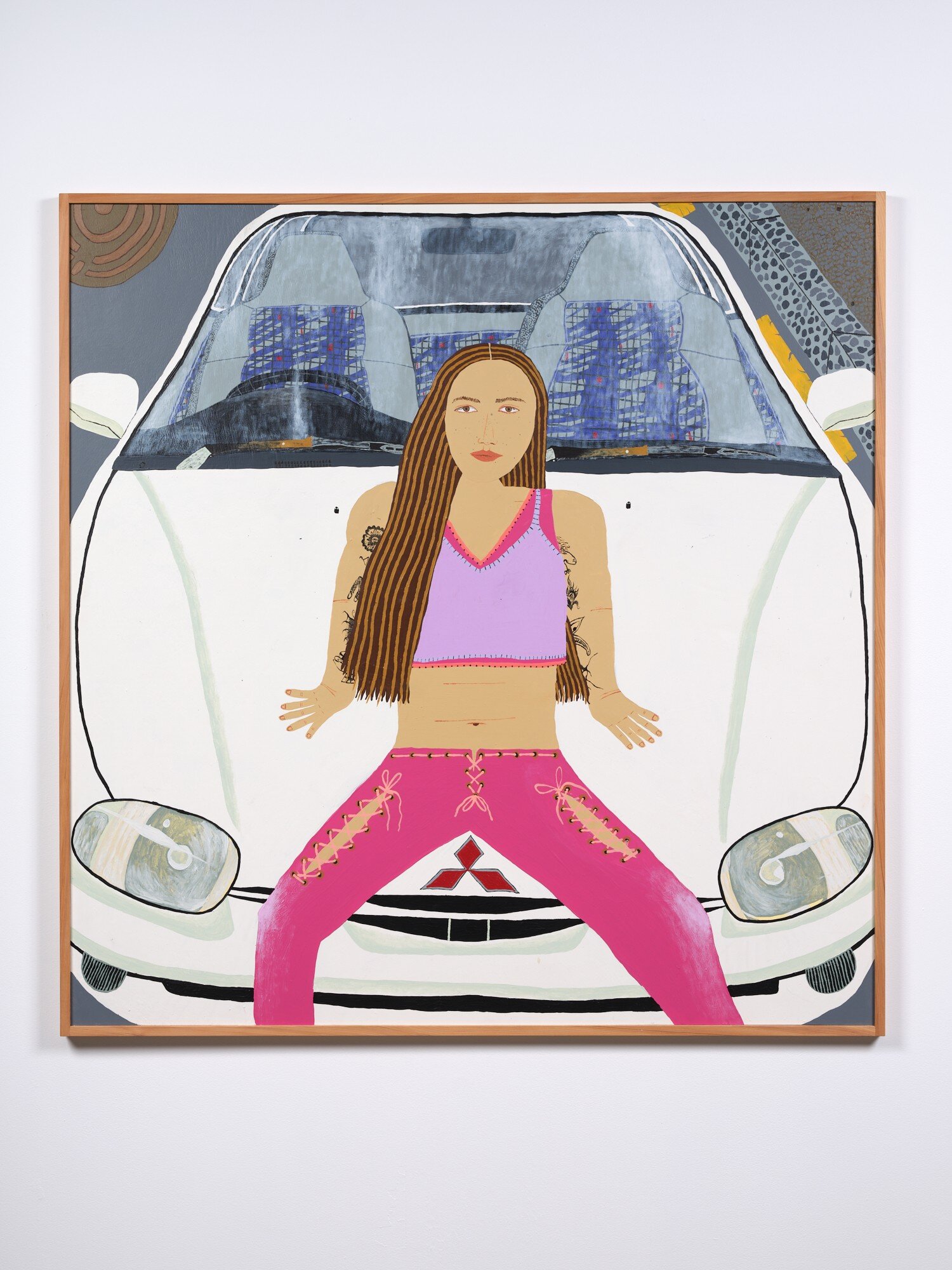

Guilty Pleasures is a new work by Bronte Perry spanning the length of Artspace Aotearoa’s East Street wall. The banners make use of digital and 3D rendering technologies to reflect on and imagine Karangahape Road’s queer night spaces: past, present and future. The following text is a conversation between Bronte Perry and Daniel John Corbett Sanders in response to Perry’s new work.

Daniel John Corbett Sanders: When I moved to Auckland in 2013 for university I was quickly picked up by gay and lesbian artists I met at art school and dragged along to the gay clubs on Karangahape Road. I was hesitant at first, and intimidated by how comfortable people were being themselves, dressing up and pulling looks I would have got the bash for back home. Their dance moves would have me quickly ending up in the emergency room. Instead, I was more at home in the random hidden places and corners of the city I found by flipping myself for cash on Craigslist. Through the often older men I met doing sex work I was taken to many offices, sex clubs, cruising spots in parks, toilets, and parties. I found myself spending more time in the back corner of a carpark with the chocolate wrappers and empty cigarette packets than I did at University. Art school wasn’t going to give me much money to live off after all, but turning a trick would. What would often come up with my older hookups and clients was nostalgic talk about the old days. Oh, how glorious it was, they would say. But looking around their houses at the beige leather la-z-boys, a sad faded drawing of a twink in a cracked wooden frame above the toilet, a kilo of chicken legs thawing on the bench next to a nearly empty bottle of Sherry—it was hard for me to imagine these glory days, especially when I was only starting to live mine.

As time went by, I met more queers and came to really get a sense of the city, it’s history, community and ancestry, often through the men I was having sex with. It turned out that it was the people at the bottom of the ‘gay barrel’ that were the face of gay culture—the trans kids, the sex workers and the queens. Unsurprisingly, these people were also the ones constantly sidelined out of the clubs, conversations, and marches. They were also the ones whose houses had been raided for selling their bodies, having hormones or a ‘fake identity.’ They were the people being beaten up, targeted by police and imprisoned.

Towards the end of 2014 I felt comfortable enough in this new gay world and attended what would be Urge Bar’s final underwear party. There I was, a skinny twink chain smoking in the corner being groped by all kinds of men and loving it before going home with a doctor. This was me living the glorious queer history I’d heard so much about. In 2015 Urge Bar on Karangahape Road closed down. Around the same time, other gay bars such as Legend closed, the neighbouring New Zealand Prostitute’s Collective had moved off Karangahape Road, and eventually, prostitution laws on the internet changed in the USA, meaning I could no longer sell myself on Craigslist—I was put out of work.

Around this time as these traditionally queer spaces were closing, I noticed that LGBTQ+ artists started occupying institutional spaces. Suddenly, queer night space became restricted to a public programme or exhibition schedule. And the queer history I knew that was about dressing up a bit trashy/sexy and hooking up with randoms in the back of a carpark for cash and survival instead became about a tedious fight for space, funding, visibility, etc. I feel like more than often, ‘queerness’ as a conceptual framework is now beholden to institutions. Sometimes all I want is Craigslist back and a back alley bar to go smoke in my undies at.

I think this is what drew me back to working in the sex industry. In 2016 I started working at Basement Specialist Adult Store and Cruise Club. Here, I’ve felt quite at home and have been supported with a genuine sense of community. I would say I am grounded in this kind of sex space or night space, and it makes the increasing conservatism of Karangahape Road bearable. And when the art industry is preoccupied with fights for space and identity, the reality in clubs such as Basement is sometimes all a girl needs is a space to make a quick buck, have a quick fck, and access the internet. Sometimes, I find solidarity simply by sharing an instant coffee with a stranger and talking absolute trash. I guess that leads me to my big question: What even is a queer space these days? And what are they even for anymore?*

Bronte Perry, Guilty Pleasures (detail), 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Artspace Aotearoa

Bronte Perry: The Karangahape Road that I think of is usually the Karangahape Road my parents and uncles knew. Both my parents grew up mainly in the city. Mum traveled regularly to Northland until she was fifteen. My other parent, Hana, also traveled up to Okaihau/Kerikeri to live with their Dad, until he died of asthma when Hana was fifteen or sixteen. So both parents were basically the first generation of urbanised kids, a part of the post-war urbanisation boom. Mum through the work training schemes that led to Maori urbanisation, and Hana through the children of middle class Pākehā farmers resettling into cities.

Karangahape Road’s infamy comes from their days in the ‘70s and ‘80s. In 1963, Railton Hastie opened his stripclub, Pink Pussy Club, in what is now Stark White gallery. The sight of his pink Cadillacs roaring down Karangahape Road brought in a new era of illustrious depravity. Whilst Fiona Clark was clocking the gender and sexual diversity of the queer scene, Mum was a child attending the congregation held in the Abbotts Chambers building. Her brothers knew the whispers of severe religious, physical and sexual abuse of Antoine Dixon. Mum remembers him sitting on the floor colouring in Batman comics at the weekly meetings. My uncle knew the elders would be waiting to beat him when he got home. Mum was scooped up in the state cleanse of inner city neighbourhoods to make way for gentrification. Unlike so many others who were forcibly sent to the new suburb of Otara by the violence of the 1974–76 dawn raids, Mum was moved to state housing in Meadowbank, bringing her time with Karangahape Road to end. I hold onto Mum’s memories because they carry the history of Karangahape Road not reflected anywhere else.

Growing up in South Auckland in a socially outcast annoying Christian group, my tangible relationship with Karangahape Road didn’t come about until I went to University. For me, University was my way out of Papakura, away from everyone who knew the old (girl lol) me, to a place where I knew there were ‘deviants,’ according to my relatives' stories. I was desperate for a place to understand myself, and to find people like myself—the people I had heard of in the stories. I wanted to fuck, and be fucked. I wanted to be messy and ugly while I figured who I was, and where I belonged. I was ready to put down the good Christian girl and be the transexual of my dreams.

I was twenty years too late to build my own relationship with Karangahape Road. Moving to the city, I really felt my class in new ways I had never experienced before, especially in the queer scene. I met my first trust fund queer, and learned what poverty aesthetics were. I learned that I couldn’t afford to live on Karangahape Road. I was heartbroken, I felt like there really was no space for me on this street as I was already classed out. Through the stories Mum tells me, I know the histories of Karangahape Road that people want to forget.

Karangahape Road is not in itself a ‘queer space’ but a place of solidarity amongst those severely othered—this created spaces for queers to thrive. I think that thinking of Karangahape Road as solely a ‘queer space’ is revisionist and a colonial understanding of Karangahape Road that flattens the complexity of it. It also erases our responsibilities to those who helped create the ‘queer spaces’ on the street—the houseless, sex workers and inner city working class communities—who have all largely been shoved out. For me, Karangahape Road is in it’s last dying days. The pace of gentrification ramps up each year, stripping and sanitising Karangahape Road one shop front and revanchist architecture at a time.

The calls to create and maintain queer spaces on Karangahape Road by my generation are often empty and performative gestures that have no material benefits for queers in the city. Karangahape Road cannot have queer spaces without, as you say, ‘queers at the bottom of barrel’ being able to attend or make a coin. I mourn the loss of Karangahape Road, but I have faith in the uglies, the houseless, the dirty fags, the sex workers, the filthy gender fuckers, the labourers and the gloriously insane to build our own spaces as we have again, and again. A whakapapa of solidarity is what binds us, not place or land.

We visited the opening event on Friday 3 May with photographer Felix Jackson.