Effervescent Dynamism/Desire and the work of Deborah Rundle

Jo Bragg on Deborah Rundle’s recent exhibition, On My Volcano Grows the Grass.

The solo exhibition by Deborah Rundle, On My Volcano Grows the Grass led its audience through an exhibition space located along the hallway and up three flights of stairs at Parasite, a gallery which, at that time, was located on Karangahape Road.

Deborah Rundle, Tephra, 2021, lava bombs. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

This reading is about the teleportational power of poetry and the force of desire. Suffice to say—given that describing the material quality of works and the interrelated spatial configuration of an entire show, really isn’t my thing–On my Volcano Grows the Grass was set up and split into three distinct sections by the landings of a stairwell winding upward. I favour something more like Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (2006), that “is motivated by an interest in the specific question of sexual orientation”, asking “what difference does it make what or who we are oriented toward in the very direction of our desire? If orientation is a matter of how we reside in space…”.(1) I am, therefore, attuned toward the poem from which the show takes its title. It latches on to the works in order to produce an affect. Put simply, I’m talking about a feeling, or an atmosphere.

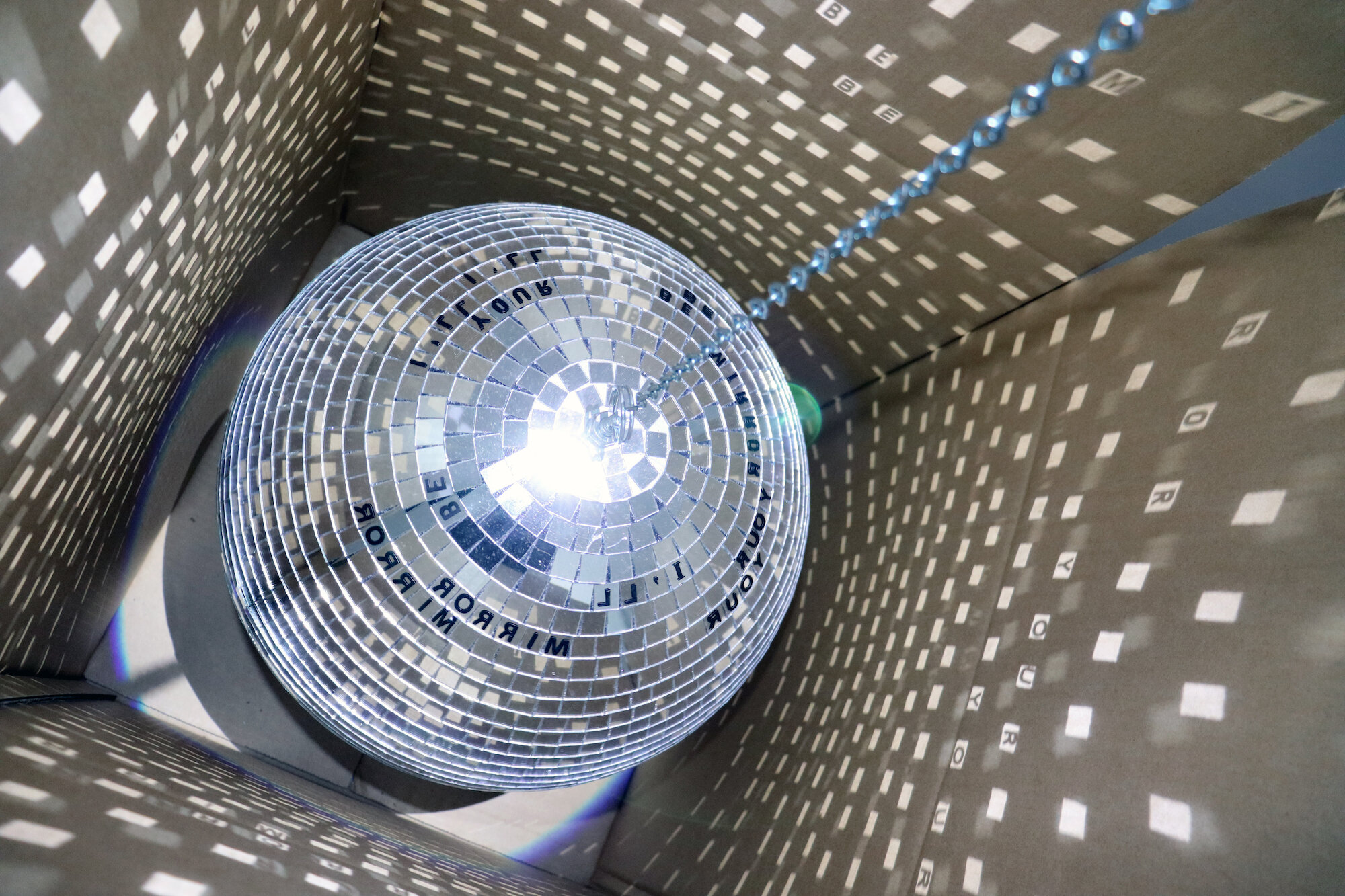

In testament to the thoughtful and dedicated research that went into every work, this show is a hard one to write about. I have no idea where to rest my attention. Do I focus on the most eye-catching: I’ll Be Your Mirror (2021), the spotlit low hanging mirror ball set spinning inside a large cardboard box? Or the reference to Lou Reed, his song of the same title with the following line “reflect what you are,” the underground; gay night club culture and the role of the dance floor in Queer history and legacy?(2) That would be, to make nothing of the small mirror hung head-height attached to the wall nearby, with the word “speculum” on its surface,(3) which alludes to the Lacanian theory of the mirror stage,(4) and the significance of multiple reflections of ‘self’ and the ‘other’ to identity formation.

Do I go upstairs and bring attention to the salacious backlit LED light work, that simply exclaims: Oh Oh (2021)? Or, do I go further up? where I reach Loss (2021) at the top of the stairs: a photograph that makes me think of the emblematic serpent ‘Ouroboros,’(5) always represented with its tail in its mouth, endlessly devouring and being reborn from itself.

In reality though, when standing in front of Loss, I’m looking at a photograph of a skink framed by artificial grass. The photograph winks at me with a suggestive implication: transform through fear. I think of the defence mechanism of this little lizard, the ability to drop its tail when distressed in order to cause distraction enough to escape and hide. The title: Loss, and the skink, photographed tailless are referential to a process–the endless forming and reforming of all things, through or beyond fear. Yet, here, at the top of these stairs, rendered still.

Trapped inside an artificial environment and rendered still, this image leads me to say the word that the works really want: Dormant. The show comes from a line in a poem by Emily Dickenson. Untitled by her, simply referred to as J1677:

On my volcano grows the Grass

A meditative spot-

An acre for a Bird to choose

Would be the General thought-

How red the Fire rocks below-

How insecure the sod

Did I disclose

Would populate with awe my solitude (6)

Jumping from the poem into the show, we are able to teleport back in time, right into the middle of some pretty iconic gossip and historic gay drama. Dickinson was infamously rumoured to have had a secret long-term love affair with her neighbour, the wife of her brother: her sister-in-law. The line, On my volcano grows the grass when read in this light, suggests not solitude, but the provisional stillness of something dormant, a rumbling under the surface: the dialectical potency of desire. As Ann Carson aptly points out “It was Sappho who first called eros bittersweet”, at once an experience of pleasure and then pain, “no one who has been in love disputes her.”(7)

Which is exactly where the work Sweet Pepper (2021) comes in. Downstairs, running down the centre of the ceiling is a series of vulvic glass chandelier teardrops, hanging just low enough to cause obstacle to the tall and underprepared. The adhesive vinyl text which accompanies these chandeliers is like a stiff drink, or a slap in the face. Sweet Pepper reads:

somewhere

the other day

smell of your cunt

teased my nose

rust pepper

tang again

in my mouth

At this point, I’m not exactly sure what to say next about why that text matters so much. I guess, Sweet Pepper (2021) is THAT moment in the show, where I rest my attention. Where poetry—which has more of a reputation for rendering things watery or more abstract—actually makes the meaning: the potency and power of desire, crystal clear.

This makes me think of Lauren Berlant's essay The Book of Love Is Long and Boring, No One Can Lift the Damn Thing . . . (2012), a blog page for SupervalentThought, which can’t be a bad thing to bring up in conclusion. In that brief essay, Berlant contemplates feeling “dissociated from all my loves.” She goes on, “I sometimes ask them to hold more of an image of me than I can hold. By ‘sometimes’ I mean all the time.”(8) Berlant captures here what desire is. The interplay between memory, interiority and exteriority, the “ask” of the poem by Emily Dickinson. The “holding of an image” which captures the power of suppressed desire which ultimately fuels its exterior animation, its effervescent dynamism. The very same power or force which, ultimately, animates this show.

Footnotes:

(1) Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006, 543.

(2) Angus McGrath. Desire and Failure: The Club, Sexuality and Queer Utopias. Runway Journal, 2018.

(3) Luce Irigaray. Speculum of the Other Woman. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1985.

(4) Jacques Lacan and Bruce Fink. Ecrits: The First Complete Edition in English. NY: W.W. Norton & Co, 2006.

(5) Ouroboro originates from Ancient Egyptian iconography. The Western term derived from Ancient Greek: οὐροβόρος, -οὐρά oura 'tail' -βορός boros 'eating'.

(6) Emily Dickinson. J1677, 1865-1886.

(7) Anne Carson. What does the lover want from love in Eros the bittersweet: an essay. Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1986, 62 – 69.

(8) Lauren Berlant. The Book of Love Is Long and Boring, No One Can Lift the Damn Thing . . . Supervalent Thought, 2012.

Deborah Rundle, Sweet Pepper (detail), 2021, glass chandelier teardrops, adhesive vinyl text. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

Deborah Rundle, Oh, Oh, 2021, MDF, backlit LED. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

Deborah Rundle, Sweet Pepper (detail), 2021, glass chandelier teardrops, adhesive vinyl text. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

Deborah Rundle, Speculum, 2021, glass mirror, sandblasted glass magnifying mirror. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

Deborah Rundle, I'll Be Your Mirror, 2021, cardboard box, mirror ball and motor, spotlight, vinyl text. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite